Maps

number twenty-five

It all seemed to easy to navigate when I was looking at it on a map, but in reality Monterrey is big and wadded up and filled with traffic. Luckily, I live thirty minutes away. 932 words.

[NL]—Nearly thirty minutes after we’d arrived in the outskirts of Monterrey, we arrived at my house. Monterrey had been pretty much what I’d been led to expect by the photos and websites I’d seen while anticipating my arrival: industrial, non-beautified, and teeming with people. It is a bustling modern metropolis, obviously slapped hastily together as it charged through its rapid expansion. In this way, it sort of seems like Mexico’s Charlotte, North Carolina; or maybe Greenville, South Carolina.

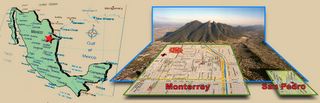

I had acquainted myself pretty well with the maps that I had seen, but was still surprised when I half knew where we were in the city as we drove through it that first time. Reality is always surprisingly different from the expectations I build when I read maps. The landscape is shockingly confused and mazelike when I am plonked down in the middle of it, instead of very flattened-out like on paper. Even in Mexico, where many places have buildings that top off at four floors, turns vertical and confusing. I know this is a pretty obvious thought, what with maps being sheets of paper, and cities being corridors of multi-colored buildings heaped on top of one another in an uneven and unplanned chaotic scatter mostly obscured behind the observer’s present vantage. Still, it is striking to me every time. In this instance, while I was wowed by the sheer size of Mexico’s third-largest city, Matt was pointing out certain landmarks outside the van’s windows (he made driving here seem easy, if not sane). I gradually realized that I knew pretty much where I was. There was the metro station, where the two public transportation lines come together. That meant that the bus station was going to be up on the right. We were going to turn left through the center of the city. The Macro Plaza, Monterrey’s answer to Mexico City’s National Zócalo, a large monument of open park space smack in the middle of downtown, was going to be up several blocks to the left after we turn. Eventually, we were going to get to the river (which is mostly a river bed), and then we would turn right and head past the Consulate. Matt confirmed everything I said. I felt at least a little less lost.

Of course, the map did not really prepare me for all of the mountains. Every picture of Monterrey seems to include its iconic Cerro de la Silla, so I was expecting “Saddle Mountain” to be looming over everything. But there’s also Cerro las Mitras to the west, and Chapenque to the south, not to mention all of the little hills and valleys Monterrey spills over and around. This means that the town is far more sprawling and jumbled than I expected it to be. Even after I had noted that Monterrey maps contain less than the average number of straight lines, and I’d assumed the reason that many of the roads seemed to merely end is because they are pointing up pretty tall slopes, the reality surprised me. Monterrey is a city of dramatic and dazzling natural backdrops, to be sure.

Somewhere in the traffic and confusion after the passing the Consulate, we picked up the road that took us under the ridge that separates the suburb of San Pedro from the center of Monterrey. On the other side of the tunnel, traffic lessened somewhat, and the buildings and landscaped greenery began to look a little more like Beverly Hills than Charlotte. Here we passed along a wide speedway of large, mostly US, shopping opportunities like T.G.I. Friday’s and Home Depot. There were a number of giant malls, banks, and grocery stores. We turned right a the Costco.

So now I am at my house for the first time. It is very, very large and dazzlingly white. Almost all of the internal walls are the same stucco-looking cement that make up the outside walls, too. Every bedroom has its own bathroom with a shower, and the entryway has a water-closet. The kitchen is enormous, with a walk-in pantry. Appliances like washers and driers and microwaves have built-in nooks for that sharper image. There is a white privacy wall around the whole rear of the house, which means I don’t have to close the blinds unless I want it dark. Most of the closest houses are a story below me down the hill we live on. I can see at least one mountain out of any window in the house. Sometimes that is all I can see. It is possible to view the famous Cerro de la Silla from the dining room table. The place is made of marble where it isn’t stucco; and, currently, it is empty like some deco Miami Vice set. When I call out to mi amiga, I echo, like, thirty-seven times.

It is a really nice pad, to be sure. It’s a nice neighborhood. But Monterrey is a disconcerting distance away, over the mountain I can see from all of the windows facing north. I am afraid that it would take me over forty minutes to get there on foot, even if I could find a way over the hill and through the traffic. San Pedro seems nice enough for the “richest neighborhood in Latin America,” a quote I can attribute to damn near everyone who lives here, but it isn’t wildly exotic. Near me there is a park, a lot of neighbors I can’t visit without explaining myself to the guard that runs the gate, and Cerro Chipenque.

And Costco. Finally, I am a member of a Costco.

[NL]—Nearly thirty minutes after we’d arrived in the outskirts of Monterrey, we arrived at my house. Monterrey had been pretty much what I’d been led to expect by the photos and websites I’d seen while anticipating my arrival: industrial, non-beautified, and teeming with people. It is a bustling modern metropolis, obviously slapped hastily together as it charged through its rapid expansion. In this way, it sort of seems like Mexico’s Charlotte, North Carolina; or maybe Greenville, South Carolina.

I had acquainted myself pretty well with the maps that I had seen, but was still surprised when I half knew where we were in the city as we drove through it that first time. Reality is always surprisingly different from the expectations I build when I read maps. The landscape is shockingly confused and mazelike when I am plonked down in the middle of it, instead of very flattened-out like on paper. Even in Mexico, where many places have buildings that top off at four floors, turns vertical and confusing. I know this is a pretty obvious thought, what with maps being sheets of paper, and cities being corridors of multi-colored buildings heaped on top of one another in an uneven and unplanned chaotic scatter mostly obscured behind the observer’s present vantage. Still, it is striking to me every time. In this instance, while I was wowed by the sheer size of Mexico’s third-largest city, Matt was pointing out certain landmarks outside the van’s windows (he made driving here seem easy, if not sane). I gradually realized that I knew pretty much where I was. There was the metro station, where the two public transportation lines come together. That meant that the bus station was going to be up on the right. We were going to turn left through the center of the city. The Macro Plaza, Monterrey’s answer to Mexico City’s National Zócalo, a large monument of open park space smack in the middle of downtown, was going to be up several blocks to the left after we turn. Eventually, we were going to get to the river (which is mostly a river bed), and then we would turn right and head past the Consulate. Matt confirmed everything I said. I felt at least a little less lost.

Of course, the map did not really prepare me for all of the mountains. Every picture of Monterrey seems to include its iconic Cerro de la Silla, so I was expecting “Saddle Mountain” to be looming over everything. But there’s also Cerro las Mitras to the west, and Chapenque to the south, not to mention all of the little hills and valleys Monterrey spills over and around. This means that the town is far more sprawling and jumbled than I expected it to be. Even after I had noted that Monterrey maps contain less than the average number of straight lines, and I’d assumed the reason that many of the roads seemed to merely end is because they are pointing up pretty tall slopes, the reality surprised me. Monterrey is a city of dramatic and dazzling natural backdrops, to be sure.

Somewhere in the traffic and confusion after the passing the Consulate, we picked up the road that took us under the ridge that separates the suburb of San Pedro from the center of Monterrey. On the other side of the tunnel, traffic lessened somewhat, and the buildings and landscaped greenery began to look a little more like Beverly Hills than Charlotte. Here we passed along a wide speedway of large, mostly US, shopping opportunities like T.G.I. Friday’s and Home Depot. There were a number of giant malls, banks, and grocery stores. We turned right a the Costco.

So now I am at my house for the first time. It is very, very large and dazzlingly white. Almost all of the internal walls are the same stucco-looking cement that make up the outside walls, too. Every bedroom has its own bathroom with a shower, and the entryway has a water-closet. The kitchen is enormous, with a walk-in pantry. Appliances like washers and driers and microwaves have built-in nooks for that sharper image. There is a white privacy wall around the whole rear of the house, which means I don’t have to close the blinds unless I want it dark. Most of the closest houses are a story below me down the hill we live on. I can see at least one mountain out of any window in the house. Sometimes that is all I can see. It is possible to view the famous Cerro de la Silla from the dining room table. The place is made of marble where it isn’t stucco; and, currently, it is empty like some deco Miami Vice set. When I call out to mi amiga, I echo, like, thirty-seven times.

It is a really nice pad, to be sure. It’s a nice neighborhood. But Monterrey is a disconcerting distance away, over the mountain I can see from all of the windows facing north. I am afraid that it would take me over forty minutes to get there on foot, even if I could find a way over the hill and through the traffic. San Pedro seems nice enough for the “richest neighborhood in Latin America,” a quote I can attribute to damn near everyone who lives here, but it isn’t wildly exotic. Near me there is a park, a lot of neighbors I can’t visit without explaining myself to the guard that runs the gate, and Cerro Chipenque.

And Costco. Finally, I am a member of a Costco.

<< Back to the Beginner.