A Note Regarding Why

number 4/2006

I was up pretty early this morning reading the news. Violence is still escalating between cartels vying for control of the northern border. Suddenly, I heard a knock at the door…. 2,896 words.

Crossroads Town

[NL]—The town of Laredo enjoys a sleepy history seemingly incommensurate with its current woes. Born alongside Spanish colonial expansion into northern territories in the eighteenth century, the area which is now Laredo was first discovered because it was an efficient place to cross the muddy Rio Grande. Soon, petitions were written, permissions granted, and a small huddle of adobe houses officially cropped up there. The residents of these houses watched as their Spanish flag was replaced by the Mexican flag after the war of independence, the Mexican then replaced with the Texan during the succession of the Lone Star Republic, and then, finally, as the Stars and Stripes were permanently hoisted at the end of the long “Mexican War,” a border dispute concerning much of Texas, California, Arizona, and New Mexico. Between these milestones, forts and battalions sprung up on the banks of this crossroad, garrisons were stationed, and Santa Ana marched through on the way to the Alamo. The little village of Laredo even enjoyed a stint as the capital of the short-lived Republic of the Rio Grande, a de facto no man’s land between the Rio Grande, America’s declared southern border, and the more northerly Nueces River, the northern border declared by Mexico. During all of this, dusty little Laredo abided as an important and all but unnoticed waypoint.

But then something fundamental happened again, making Laredo pretty much unique, and somewhat determining the constancy of its difficult future. When the US finally convinced Mexico to recognize the Rio Grande as the border between the two countries, little Laredo, sitting on the river’s fertile northern floodplain, with its Spanish then Mexican heritage, was left in the wrong country. In response, patriotic Mexicans moved south of the river to retain their Mexican citizenship, and a new dusty little settlement was born: Nuevo Laredo. Throughout the years, these two Laredos have been inextricably tied together—the archetypical border towns facing each other across federal checkpoints and an intermittent river, evincing the worst of two worlds as a sibling love/hate thing. Together, they’ve seen cattle booms and onion booms and oil booms and tourist booms. Both have grown into medium-sized cities, with populations in the hundreds of thousands. Each has played its part as the other city’s exotic wild frontier, while both have sought to attract international attention through urban beautification, commercial opportunity, and an environment of multi-nationalism.

Newest Boom

A quick summary of Mexican drug trafficking is a difficult undertaking because the illegal drug trade here has a long and varied history. Any attempt to pair that history into a meaningful brief is arbitrary and quixotic, picking and choosing from the daily struggles of hundreds of players over six decades of crime. Still, I will attempt to make some sense of the pertinent details of the last twelve years, starting in 1993 when there were still about eight major narcotics syndicates running things in the north of Mexico, smuggling drugs into the US at the behest of Colombian cartels. Colombian cartels had been having a tough time of it, with the US War on Drugs cracking down on production in Colombia and shutting down trade routes through the Caribbean. By 1993, Mexican syndicates were picking up the smuggling and distribution slack with Colombia’s blessing, widening land routes across the northern border. Three Mexican Syndicates emerged from this new situation dominating the drug smuggling scene: the Juarez Cartel lead by Amado Carillo Fuentes, the Gulf Cartel led by ex-Mexican State Policeman Osiel Cardinas, and the Tijuana Cartel led by the Arellano Felix brothers, Benjamin and Ramon.

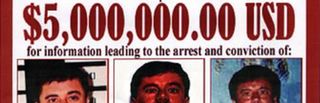

This Tijuana Cartel controlled the shipping routes into Southern California and along the Pacific coast of Baja California. Vying for power in the states of Sinaloa and Sonora, and revolutionizing trafficking through the implementation of state-of-the-art tunnels into Arizona, is the so-called Sinaloa Cartel, run by Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, a former enforcer for the Juarez cartel, and Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, his stepbrother. This makes for bitter enemies in the Mexican underworld, and the Arellano Felix brothers attempt to have El Chapo Guzman assassinated in Guadalajara in May 1993, accidentally killing a beloved catholic cardinal instead. This lead to both an enormous public outcry—prompting the Mexican government to put the screws on the northern ganglands—as well as the arrest and imprisonment of Sinaloa clan’s El Chapo.

By 1997 these federal crackdowns within Mexico had made things tougher for the local cartels. The corrupt head of Mexico's anti-drug agency, Gen. Jesus Gutierrez Rebollo, had been caught and jailed for allegedly being a cartel puppet. Federal agents and special forces were hampering trafficking across the border in strategic areas. Then, Juarez Cartel leader Amado Carillo Fuentes died during a botched attempt to change his appearance using plastic surgery, throwing the most powerful Mexican drug syndicate into supposed decline. Controlling the east coast syndicates, the Gulf Cartel honcho Osiel Cardinas was being harried by federal troops in his richest markets, Nuevo Laredo and Matamoros (across the border form Brownsville, Texas). Unconcerned, Cardinas enticed a bunch of these federal crime fighters, all military special forces, to desert the government cause and hire on as his own personal army of elite narco-terrorists. Once recruited, these enforcers began to recruit and train new people, and they rechristened themselves Los Zetas after a Mexican Army radio call code for “commander.”

But the Juarez Cartel was just biding its time. While shopping around for a new boss, it was situating its own people in corrupt high places, and rebuilding itself to its former glory with acts of drug-trade espionage. During 1998-9, the ruling party in Mexico, the PRI, was gearing up for the first election it would lose in seventy years, and Mexico was seeing a time of municipal change. By the time the PAN’s Vicente Fox took the oath of office in 2000, the Juarez Cartel was back to being bigger, and better placed, than any two of its regional competitors, rivaled only by the Gulf Cartel on the other side of the country. President Fox, in a showy effort to continue Mexico’s fight against its crime-riddled north, and in a show of cooperation with certain international drug initiatives, commenced a campaign in conjunction with US anti-drug agents that landed hundreds of wanted smugglers in jail, many of them high-placed cartel leadership. Mysteriously, this federal onslaught was most effective against all but the Juarez Cartel which was able to grow in the face of its competitors’ bad luck. In 2001, post September 11th reforms at US entry points effectively ended any ability to smuggle southern narcotics into the country other than by land from México, putting northern Mexican cartels in a position to control much more of the drug trade than ever before. Mexican syndicates creep over the border to control distribution and further trade through the US; but the statistics of drug use below the border also rises, the bottlenecked supply finding the point of least resistance in Mexican markets. Also in 2001, with the aid of El Mayo Zambada, Sinaloa Cartel honcho El Chapo Guzman successfully conducts a sensational escape from La Palma maximum security prison, hiding in a laundry truck and being delivered through the gates.* Thirty of the guards at La Palma, as well as the prison’s warden, are arrested and indicted.

By the end of 2002, federal dragnets have paid off big: Ramon Arellano Felix has been killed and his brother Benjamin jailed. By March of 2003 even the head of the powerful Gulf Cartel, Osiel Cardinas, has been arrested after a vicious shootout on the streets of Matamoros. This leaves a power vacuum that proves to be too tempting to both the re-emerging Juarez and the Sinaloan Cartels, and both seek to grab it from different directions. The Juarez Cartel makes a pact with El Mayo Zambada to attempt to gain control of the teetering and newly headless Tijuana Cartel to the west, while it directly attacks the lucrative trade routes of the newly headless Gulf Cartel in the east. The newly liberated El Chapo Guzman splinters off and, setting up shop in the state of Tamaulipas, begins a long and bloody campaign to flank these Gulf Cartel holdings from the east; attacking, primarily, Nuevo Laredo and its resident ex-military Zeta enforcers.

So the area is booming again. Big business for whoever ends up with control of America’s 165 million dollar a day drug habit, a vast majority of which is supplied to US distribution channels through the streets of Laredo. This former tough frontier-land joint and latter day revitalized shopping district is the most lucrative inroad to the US drug market, now handled primarily by Mexican Cartels on both sides of the border. Since 1935 the Pan American highway has connected it to the capital cities of Central America and Mexico, and just on the other side of the river US I-35 begins, a ribbon of asphalt that doesn’t stop until it reaches Lake Superior. Six thousand tractor trailers truck forty percent of Mexican exports over the three international bridges that connect the two Laredos every day. It is a drug smuggler’s paradise, and that is why El Chapo is fighting so hard to gain a territory that the imprisoned Osiel Cardinas and his autonomous gang of Zetas are tying so hard to keep. Caught in the crossfire, the people of Nuevo Laredo are grimly bearing witness to a staggering wave of violence. Charred bodies turn up in barrels on the sides of the highways weekly; firefights, between warring factions or police, take over busy streets in broad daylight. Reporters are threatened, kidnapped, even killed in retaliation for reporting these excesses to the rest of the world, newspaper offices are sprayed with bullets by the roving bands of enforcers. The Zetas roam the city in the backs of pickup trucks bristling with automatic weapons, strong-arming local businesses out of protection money, staging roadblocks, and in general running a lawless town their own way.

Things are similar in other border towns. Osiel Cardinas is apparently able to run his Gulf Cartel from his prison cell, as is Benjamin Arellano Felix. Their turf has not been left as unprotected as everyone originally assumed. In La Palma maximum security prison, after years of bitter rivalry, the two bosses were able to hash out an alliance to strengthen their respective syndicates; though they were separated after violence erupted in 2004, forcing the government to federalize the prison. Several of the most notorious prisoners were moved to a border prison in Matamoros where, a few days later, on New Year’s Eve 2004, El Chapo Guzman’s brother Arturo was murdered. There were more federal crackdowns there, of course, and twenty days later six prison guards were discovered a short distance from the jail tied up and shot in the back of a Ford four by four.

In 2005, Nuevo Laredo’s police chief quit and it took authorities until June to find someone brave enough to replace him. That man took office on the afternoon of the eighth and was gunned down in a parking lot less than eight hours later, so Nuevo Laredo was looking for yet another police chief. Federal agents involved in the inevitable crackdown, called “Operation Secure Mexico,” were fired on, with one agent wounded, by legitimate city police so confused and brutalized by two years of this conflict that they just shoot at any invading army. This prompted the government to suspend Nuevo Laredo’s entire police force of six hundred officers pending drug tests and criminal investigations. Six months later, less than half were allowed, or would volunteer, to return to the streets. By this writing, there is a new police chief who has remained alive in the position for seven months.

There is news of violence or brutal murder along the northeastern border daily. What is represented here is just a small sample, quixotically and arbitrarily plucked from the trove of available information. Mexico’s fight against the situation here, escalating to a fever-pitch in this election year, has come under proverbial fire for simply doing nothing but providing more troops for the mobsters in Nuevo Laredo to recruit. Violence from this territory war has spilled north into the US as far as Dallas, and south to all corners of Mexico, where secondary players are fighting for the jobs being left behind by the war’s casualties. Central American youth gangs like Mara Salvatrucha and the 18th Street Gang are crossing the border to hire themselves out as Mexican cartel enforcement. So are members of elite Guatemalan military units. All over Latin America, this run for the border is causing ripples of violence within the world of illegal drugs. But in the border city of Nuevo Laredo, the violence has long spilled into the everyone’s world. There the police, the reporters, the citizens, the federal agents, the politicians, and the drug lords are all getting killed. There were about one hundred and seventy unsolved murders in Nuevo Laredo last year. There have been over fifty already this year.

Shorty and Me

So far this violence has only rarely made the 225 kilometer trip down the highway to Monterrey. Here, the city feels poised for this eventuality, but has remained relatively untouched. There have been a few shootouts here, one in a popular local seafood restaurant shortly before I arrived, and one in a Dave and Busters down the road, apparently connected to the killings in Dallas referred to above. Bodies have turned up in Guadalupe, a suburb located at the base of Monterrey’s most iconic mountain. Our local Police chief was killed in heavy traffic in February (on the same day another police chief was killed in another little town off the highway between here and the border), and raids on local residences have produced caches of military-style weapons and groups of reinforcements apparently stopping over in route to the war up the road. All of the instances of violence here have been very premeditated and very much focused on targets within the narcotics trade. There is currently very little feeling of danger on the streets of Monterrey.

Of course, we are all very much on alert. The State Department has issued advisory after advisory warning US citizens of the situation in Nuevo Laredo. The US Consulate there closed its doors for a week in August of last year after an afternoon shootout on a busy nearby street. In Monterrey, Sunshine’s employers have begun to implement a heightened security routine including check-ins whenever traveling out of town. For me, the sole effect of all this violence has been that for three days I have had to get up at seven in the morning because professionals from the alarm company have been in the house, eight hours a day, grinding holes through my walls and running brightly colored wires everywhere. The three-foot masonry drills they use scream from every room in the house, and occasionally they test something that howls like a monster version of some ray gun toy I might have annoyed my parents with when I was nine. There are tall piles of plaster dust everywhere and all of my closets have been emptied out onto the bed. The cat has been wedged tightly between the wooden slats beneath our futon for days, eyes shut, counting the years being scared off the end of her life.

I have been recruited to oversee this contracted labor, leaving me with plenty of time between curdlings of my nerves to ask, well, “why?”. It seems rather ridiculous to me, in this posh neighborhood, behind electric iron gates (which are situated on an incline and open inward like all the security books say the should) with a twenty-four hour guard, that I would also need a alarm system. It would be incredibly difficult to scale the sixteen-foot privacy wall in the back yard (assuming it is possible to break into the neighbor’s gated community). Anyone getting in here will have to hurdle some serious odds. I’m not saying it isn’t possible; but whomever makes it to my front door is going to be sufficiently sly, or sufficiently well-armed, to be unconcerned with the toy gun that will go off when a window breaks. No, more likely it’ll be me who trips the alarm through no more dastardly a crime than sleepily pressing the wrong code into the complicated wall interfaces that have cropped up here and there, and then I will have plenty of Español explaining to do when the police arrive. Still, I appreciate the spirit of concern for Sunshine’s and my security, and as soon as I am awake, I will certainly feel even more comfortable in my still very safe city due to this drilling. While I am still very sleepy, though, I felt the need to dig up a twenty-eight hundred word excuse for missing so much sleep.

Further Reading about the Mexican drug trade.

Fun interactive Mexican Drug information produced by PBS

*Interestingly, in Mexico there is no law against breaking, or attempting to break, out of prison. Other laws broken in the commission of a jailbreak can be charged when or if the fugitive comes to justice; but in Mexico personal freedom is deemed an attribute so worth fighting for that the law very romantically makes no provision against its being sought by the incarcerated.

[NL]—The town of Laredo enjoys a sleepy history seemingly incommensurate with its current woes. Born alongside Spanish colonial expansion into northern territories in the eighteenth century, the area which is now Laredo was first discovered because it was an efficient place to cross the muddy Rio Grande. Soon, petitions were written, permissions granted, and a small huddle of adobe houses officially cropped up there. The residents of these houses watched as their Spanish flag was replaced by the Mexican flag after the war of independence, the Mexican then replaced with the Texan during the succession of the Lone Star Republic, and then, finally, as the Stars and Stripes were permanently hoisted at the end of the long “Mexican War,” a border dispute concerning much of Texas, California, Arizona, and New Mexico. Between these milestones, forts and battalions sprung up on the banks of this crossroad, garrisons were stationed, and Santa Ana marched through on the way to the Alamo. The little village of Laredo even enjoyed a stint as the capital of the short-lived Republic of the Rio Grande, a de facto no man’s land between the Rio Grande, America’s declared southern border, and the more northerly Nueces River, the northern border declared by Mexico. During all of this, dusty little Laredo abided as an important and all but unnoticed waypoint.

But then something fundamental happened again, making Laredo pretty much unique, and somewhat determining the constancy of its difficult future. When the US finally convinced Mexico to recognize the Rio Grande as the border between the two countries, little Laredo, sitting on the river’s fertile northern floodplain, with its Spanish then Mexican heritage, was left in the wrong country. In response, patriotic Mexicans moved south of the river to retain their Mexican citizenship, and a new dusty little settlement was born: Nuevo Laredo. Throughout the years, these two Laredos have been inextricably tied together—the archetypical border towns facing each other across federal checkpoints and an intermittent river, evincing the worst of two worlds as a sibling love/hate thing. Together, they’ve seen cattle booms and onion booms and oil booms and tourist booms. Both have grown into medium-sized cities, with populations in the hundreds of thousands. Each has played its part as the other city’s exotic wild frontier, while both have sought to attract international attention through urban beautification, commercial opportunity, and an environment of multi-nationalism.

Newest Boom

A quick summary of Mexican drug trafficking is a difficult undertaking because the illegal drug trade here has a long and varied history. Any attempt to pair that history into a meaningful brief is arbitrary and quixotic, picking and choosing from the daily struggles of hundreds of players over six decades of crime. Still, I will attempt to make some sense of the pertinent details of the last twelve years, starting in 1993 when there were still about eight major narcotics syndicates running things in the north of Mexico, smuggling drugs into the US at the behest of Colombian cartels. Colombian cartels had been having a tough time of it, with the US War on Drugs cracking down on production in Colombia and shutting down trade routes through the Caribbean. By 1993, Mexican syndicates were picking up the smuggling and distribution slack with Colombia’s blessing, widening land routes across the northern border. Three Mexican Syndicates emerged from this new situation dominating the drug smuggling scene: the Juarez Cartel lead by Amado Carillo Fuentes, the Gulf Cartel led by ex-Mexican State Policeman Osiel Cardinas, and the Tijuana Cartel led by the Arellano Felix brothers, Benjamin and Ramon.

This Tijuana Cartel controlled the shipping routes into Southern California and along the Pacific coast of Baja California. Vying for power in the states of Sinaloa and Sonora, and revolutionizing trafficking through the implementation of state-of-the-art tunnels into Arizona, is the so-called Sinaloa Cartel, run by Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, a former enforcer for the Juarez cartel, and Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, his stepbrother. This makes for bitter enemies in the Mexican underworld, and the Arellano Felix brothers attempt to have El Chapo Guzman assassinated in Guadalajara in May 1993, accidentally killing a beloved catholic cardinal instead. This lead to both an enormous public outcry—prompting the Mexican government to put the screws on the northern ganglands—as well as the arrest and imprisonment of Sinaloa clan’s El Chapo.

By 1997 these federal crackdowns within Mexico had made things tougher for the local cartels. The corrupt head of Mexico's anti-drug agency, Gen. Jesus Gutierrez Rebollo, had been caught and jailed for allegedly being a cartel puppet. Federal agents and special forces were hampering trafficking across the border in strategic areas. Then, Juarez Cartel leader Amado Carillo Fuentes died during a botched attempt to change his appearance using plastic surgery, throwing the most powerful Mexican drug syndicate into supposed decline. Controlling the east coast syndicates, the Gulf Cartel honcho Osiel Cardinas was being harried by federal troops in his richest markets, Nuevo Laredo and Matamoros (across the border form Brownsville, Texas). Unconcerned, Cardinas enticed a bunch of these federal crime fighters, all military special forces, to desert the government cause and hire on as his own personal army of elite narco-terrorists. Once recruited, these enforcers began to recruit and train new people, and they rechristened themselves Los Zetas after a Mexican Army radio call code for “commander.”

But the Juarez Cartel was just biding its time. While shopping around for a new boss, it was situating its own people in corrupt high places, and rebuilding itself to its former glory with acts of drug-trade espionage. During 1998-9, the ruling party in Mexico, the PRI, was gearing up for the first election it would lose in seventy years, and Mexico was seeing a time of municipal change. By the time the PAN’s Vicente Fox took the oath of office in 2000, the Juarez Cartel was back to being bigger, and better placed, than any two of its regional competitors, rivaled only by the Gulf Cartel on the other side of the country. President Fox, in a showy effort to continue Mexico’s fight against its crime-riddled north, and in a show of cooperation with certain international drug initiatives, commenced a campaign in conjunction with US anti-drug agents that landed hundreds of wanted smugglers in jail, many of them high-placed cartel leadership. Mysteriously, this federal onslaught was most effective against all but the Juarez Cartel which was able to grow in the face of its competitors’ bad luck. In 2001, post September 11th reforms at US entry points effectively ended any ability to smuggle southern narcotics into the country other than by land from México, putting northern Mexican cartels in a position to control much more of the drug trade than ever before. Mexican syndicates creep over the border to control distribution and further trade through the US; but the statistics of drug use below the border also rises, the bottlenecked supply finding the point of least resistance in Mexican markets. Also in 2001, with the aid of El Mayo Zambada, Sinaloa Cartel honcho El Chapo Guzman successfully conducts a sensational escape from La Palma maximum security prison, hiding in a laundry truck and being delivered through the gates.* Thirty of the guards at La Palma, as well as the prison’s warden, are arrested and indicted.

By the end of 2002, federal dragnets have paid off big: Ramon Arellano Felix has been killed and his brother Benjamin jailed. By March of 2003 even the head of the powerful Gulf Cartel, Osiel Cardinas, has been arrested after a vicious shootout on the streets of Matamoros. This leaves a power vacuum that proves to be too tempting to both the re-emerging Juarez and the Sinaloan Cartels, and both seek to grab it from different directions. The Juarez Cartel makes a pact with El Mayo Zambada to attempt to gain control of the teetering and newly headless Tijuana Cartel to the west, while it directly attacks the lucrative trade routes of the newly headless Gulf Cartel in the east. The newly liberated El Chapo Guzman splinters off and, setting up shop in the state of Tamaulipas, begins a long and bloody campaign to flank these Gulf Cartel holdings from the east; attacking, primarily, Nuevo Laredo and its resident ex-military Zeta enforcers.

So the area is booming again. Big business for whoever ends up with control of America’s 165 million dollar a day drug habit, a vast majority of which is supplied to US distribution channels through the streets of Laredo. This former tough frontier-land joint and latter day revitalized shopping district is the most lucrative inroad to the US drug market, now handled primarily by Mexican Cartels on both sides of the border. Since 1935 the Pan American highway has connected it to the capital cities of Central America and Mexico, and just on the other side of the river US I-35 begins, a ribbon of asphalt that doesn’t stop until it reaches Lake Superior. Six thousand tractor trailers truck forty percent of Mexican exports over the three international bridges that connect the two Laredos every day. It is a drug smuggler’s paradise, and that is why El Chapo is fighting so hard to gain a territory that the imprisoned Osiel Cardinas and his autonomous gang of Zetas are tying so hard to keep. Caught in the crossfire, the people of Nuevo Laredo are grimly bearing witness to a staggering wave of violence. Charred bodies turn up in barrels on the sides of the highways weekly; firefights, between warring factions or police, take over busy streets in broad daylight. Reporters are threatened, kidnapped, even killed in retaliation for reporting these excesses to the rest of the world, newspaper offices are sprayed with bullets by the roving bands of enforcers. The Zetas roam the city in the backs of pickup trucks bristling with automatic weapons, strong-arming local businesses out of protection money, staging roadblocks, and in general running a lawless town their own way.

Things are similar in other border towns. Osiel Cardinas is apparently able to run his Gulf Cartel from his prison cell, as is Benjamin Arellano Felix. Their turf has not been left as unprotected as everyone originally assumed. In La Palma maximum security prison, after years of bitter rivalry, the two bosses were able to hash out an alliance to strengthen their respective syndicates; though they were separated after violence erupted in 2004, forcing the government to federalize the prison. Several of the most notorious prisoners were moved to a border prison in Matamoros where, a few days later, on New Year’s Eve 2004, El Chapo Guzman’s brother Arturo was murdered. There were more federal crackdowns there, of course, and twenty days later six prison guards were discovered a short distance from the jail tied up and shot in the back of a Ford four by four.

In 2005, Nuevo Laredo’s police chief quit and it took authorities until June to find someone brave enough to replace him. That man took office on the afternoon of the eighth and was gunned down in a parking lot less than eight hours later, so Nuevo Laredo was looking for yet another police chief. Federal agents involved in the inevitable crackdown, called “Operation Secure Mexico,” were fired on, with one agent wounded, by legitimate city police so confused and brutalized by two years of this conflict that they just shoot at any invading army. This prompted the government to suspend Nuevo Laredo’s entire police force of six hundred officers pending drug tests and criminal investigations. Six months later, less than half were allowed, or would volunteer, to return to the streets. By this writing, there is a new police chief who has remained alive in the position for seven months.

There is news of violence or brutal murder along the northeastern border daily. What is represented here is just a small sample, quixotically and arbitrarily plucked from the trove of available information. Mexico’s fight against the situation here, escalating to a fever-pitch in this election year, has come under proverbial fire for simply doing nothing but providing more troops for the mobsters in Nuevo Laredo to recruit. Violence from this territory war has spilled north into the US as far as Dallas, and south to all corners of Mexico, where secondary players are fighting for the jobs being left behind by the war’s casualties. Central American youth gangs like Mara Salvatrucha and the 18th Street Gang are crossing the border to hire themselves out as Mexican cartel enforcement. So are members of elite Guatemalan military units. All over Latin America, this run for the border is causing ripples of violence within the world of illegal drugs. But in the border city of Nuevo Laredo, the violence has long spilled into the everyone’s world. There the police, the reporters, the citizens, the federal agents, the politicians, and the drug lords are all getting killed. There were about one hundred and seventy unsolved murders in Nuevo Laredo last year. There have been over fifty already this year.

Shorty and Me

So far this violence has only rarely made the 225 kilometer trip down the highway to Monterrey. Here, the city feels poised for this eventuality, but has remained relatively untouched. There have been a few shootouts here, one in a popular local seafood restaurant shortly before I arrived, and one in a Dave and Busters down the road, apparently connected to the killings in Dallas referred to above. Bodies have turned up in Guadalupe, a suburb located at the base of Monterrey’s most iconic mountain. Our local Police chief was killed in heavy traffic in February (on the same day another police chief was killed in another little town off the highway between here and the border), and raids on local residences have produced caches of military-style weapons and groups of reinforcements apparently stopping over in route to the war up the road. All of the instances of violence here have been very premeditated and very much focused on targets within the narcotics trade. There is currently very little feeling of danger on the streets of Monterrey.

Of course, we are all very much on alert. The State Department has issued advisory after advisory warning US citizens of the situation in Nuevo Laredo. The US Consulate there closed its doors for a week in August of last year after an afternoon shootout on a busy nearby street. In Monterrey, Sunshine’s employers have begun to implement a heightened security routine including check-ins whenever traveling out of town. For me, the sole effect of all this violence has been that for three days I have had to get up at seven in the morning because professionals from the alarm company have been in the house, eight hours a day, grinding holes through my walls and running brightly colored wires everywhere. The three-foot masonry drills they use scream from every room in the house, and occasionally they test something that howls like a monster version of some ray gun toy I might have annoyed my parents with when I was nine. There are tall piles of plaster dust everywhere and all of my closets have been emptied out onto the bed. The cat has been wedged tightly between the wooden slats beneath our futon for days, eyes shut, counting the years being scared off the end of her life.

I have been recruited to oversee this contracted labor, leaving me with plenty of time between curdlings of my nerves to ask, well, “why?”. It seems rather ridiculous to me, in this posh neighborhood, behind electric iron gates (which are situated on an incline and open inward like all the security books say the should) with a twenty-four hour guard, that I would also need a alarm system. It would be incredibly difficult to scale the sixteen-foot privacy wall in the back yard (assuming it is possible to break into the neighbor’s gated community). Anyone getting in here will have to hurdle some serious odds. I’m not saying it isn’t possible; but whomever makes it to my front door is going to be sufficiently sly, or sufficiently well-armed, to be unconcerned with the toy gun that will go off when a window breaks. No, more likely it’ll be me who trips the alarm through no more dastardly a crime than sleepily pressing the wrong code into the complicated wall interfaces that have cropped up here and there, and then I will have plenty of Español explaining to do when the police arrive. Still, I appreciate the spirit of concern for Sunshine’s and my security, and as soon as I am awake, I will certainly feel even more comfortable in my still very safe city due to this drilling. While I am still very sleepy, though, I felt the need to dig up a twenty-eight hundred word excuse for missing so much sleep.

Further Reading about the Mexican drug trade.

Fun interactive Mexican Drug information produced by PBS

*Interestingly, in Mexico there is no law against breaking, or attempting to break, out of prison. Other laws broken in the commission of a jailbreak can be charged when or if the fugitive comes to justice; but in Mexico personal freedom is deemed an attribute so worth fighting for that the law very romantically makes no provision against its being sought by the incarcerated.

<< Back to the Beginner.